Did Plennie Wingo make any progress going backward?

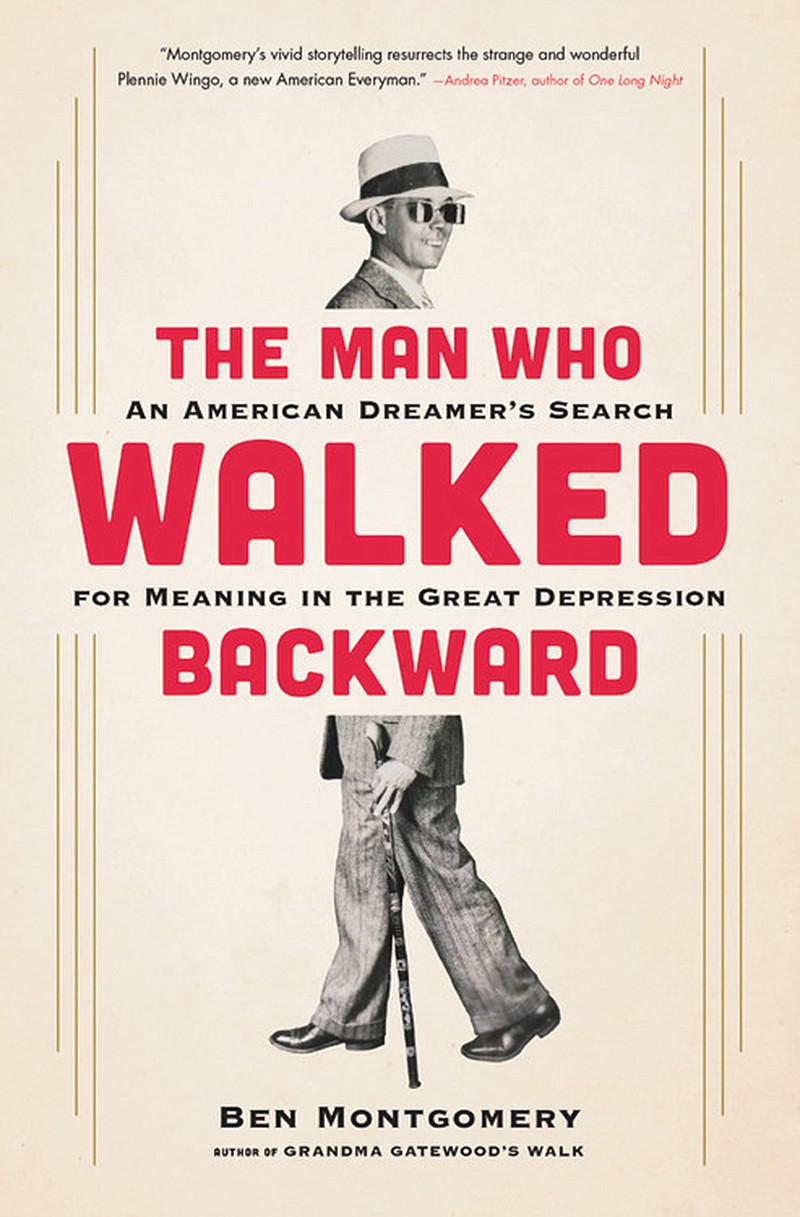

That's the question at the heart of "The Man Who Walked Backward: An American Dreamer's Search for Meaning in the Great Depression," an engaging new book by former Tampa Bay Times staff writer Ben Montgomery.

Montgomery, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 2010 for a series of articles on abuses at the Florida School for Boys, has published two other nonfiction books, Grandma Gatewood's "Walk" and "The Leper Spy," both true stories of ordinary people who did extraordinary things.

Wingo is another such subject, a real person who undertook a feat never before attempted: walking around the world backward. As the Great Depression ground down the nation and the Dust Bowl's storms darkened his home state of Texas, the nattily dressed Wingo stepped out heel-first to see the world.

Plennie Wingo was born in 1895 near Abilene, on the southern reaches of the Great Plains. His father died months after he was born; his mother briskly married her late husband's brother and went on to have a dozen children all told. By the time Plennie was 20 he had married Idella Richards; their only child, daughter Vivian, was born in 1915. In the booming 1920s, affable Plennie did pretty well as a cafe owner in Abilene. But Prohibition was in effect.

"In Texas," Montgomery writes, "substantially more than half of all cases brought to court in 1928 revolved around booze: the making, the selling, the carrying or the drinking." Plennie became one of them, charged with "selling and possessing intoxicating liquor."

On the heels of that setback came the stock market crash of 1929, leading to the Great Depression. The environmental and agricultural devastation of the Dust Bowl intensified the economic crash. Plennie, like millions of other Americans, searched for a way to survive.

He took inspiration from that decade's version of reality TV and internet memes: "The public's appetite for all things trivial could not be quenched." It was an era of crazes for newfangled crossword puzzles, celebrity gossip, dance marathons, wing walkers, flagpole sitters and anything that made the panels of the syndicated Ripley's Believe It or Not! cartoons.

Plennie had also had a close-up look at the enormous public reception that greeted pilot Charles Lindbergh in Abilene, four months after his trans-Atlantic flight in 1927. "The event was so big that the Abilene Morning Reporter-News published its largest paper ever at 102 pages, heralding 'Lindbergh Day' with a special section," Montgomery writes.

So, as Plennie told it ever after, one day when he overheard his teenage daughter's friends talking about amazing feats people had already accomplished, he was struck with inspiration: He would walk around the world-and he'd do it backward. It would, he reasoned, be a retrograde route to adventure, fame and maybe even fortune.

He began training, at first in the wee hours so neighbors wouldn't see him. One vexing problem was the mirror he held up in one hand so he could see where he was going-it was tiring to hang on to it.

"The answer," Montgomery writes, "appeared a few days later, almost like magic, in the back of a magazine. An advertisement featured a pair of sunglasses with small mirrors affixed to each side, meant for motorcyclists and sports car drivers for extra safety. Plennie couldn't believe it, took it as a sign that this was meant to be."

In the spring of 1931, at the age of 36, Plennie dressed for departure in a suit and tie, a crisp white shirt, shiny black shoes, a white Stetson and those mirror sunglasses. "If a man aimed to walk backward around the world, best to leave no doubt in the minds of passersby that he was doing so with purpose."

In clean, briskly paced prose, Montgomery follows Plennie's journey, and he walks the reader backward, too, into the history of America in the 1930s and before.

As Plennie backsteps through Texas, Oklahoma and Missouri, the author describes the line that leads from the bloody means by which white settlers wrested the Plains from Native Americans directly to the Dust Bowl.

When Plennie passes through St. Louis, Montgomery writes about the beer industry, created largely by German immigrants, that the city was built on and how it was dealt a one-two punch by anti-German policies and passions during World War I and by Prohibition: "The number of breweries in the U.S. making full-strength beer fell from 1,300 in 1916 to none in 1926."

In Chicago, Plennie makes an appearance in the first Universal Newsreel, shown in movie theaters around the world. He was already gaining fame through newspaper stories written as he passed through various cities, which appeared in papers "as far away as London and Paris."

Plennie's knack for backing into history continued as he made it to Germany in 1932. On the day Adolph Hitler announced he would run for president, Montgomery writes, Plennie "walked backward into Berlin."

Although Plennie traveled through dire times, many of the individuals he encountered were generous, offering him meals, hotel rooms, cash and clothes. He liked to entertain them in exchange. Once, in a barbecue joint in Illinois, he "felt folks watching him so he gave them a little treat. He ate the dessert first, then the vegetable, then the barbecue sandwich, then the salad, then the soup, then drank his entire iced tea."

Not everyone was entertained. When he broke an ankle stepping backward into a pothole in Ohio, the doctor who treated him groused, "Well he ought to have broken his ankle then, if he was doing that."

Ostensibly, one reason for the trip was to make money, some of which Plennie would send home to his wife and daughter. He did a brisk business in postcards with his photo on them, and he occasionally was paid to carry an advertising sign as he walked. If he were making his trek today, he'd have live feeds all over social media and a sponsorship from Fitbit. But in the '30s the sponsorships he hoped for never materialized, and little cash made it back to Abilene.

In Pennsylvania, Plennie got a fateful letter, Montgomery writes. "Della had not yet expressed the outrage a reasonable woman might have felt if her husband of sixteen years and the father of her teenage daughter had packed a suitcase and left home in the thick of what was one of the worst and most difficult years in the history of man."

Now she did, and Plennie found himself divorced. He kept going, across the Atlantic to Europe. But his grand plan to cross China and sail the Pacific to complete his U.S. route from the west was halted when he was arrested in Turkey. Via somewhat mysterious means, he got back to California and, step by backward step, to Abilene in late 1932.

Plennie moved forward, making amends with his family and remarrying Della, then later redivorcing her. He ran restaurants again; for a while, in the early 1940s, he disappeared for several years, then showed up on a sister's doorstep.

In 1946, when Plennie was 51, he married 18-year-old Juanita Billlingsley, a marriage that would last for 45 years. He wrote a book about his travels, but it never sold many copies. Occasionally he slipped back into the spotlight, making a 400-mile backward walk in California when he was 81, appearing on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson in the same year.

Plennie Wingo died in poverty, Montgomery tells us, in 1993, at age 98. If he ever expressed the deeper philosophical meaning for his treks, Montgomery didn't find evidence of it. But maybe it is the journey that's important after all, not the destination or the reason for making it, even backward.

Maybe the answer is in an interview Plennie gave after he came home to Abilene in 1932: "I walked backward about seven thousand miles, saw most of America and Europe, added, I believe, ten years to my life, managed to eat every day, met thousands of interesting people, saw many wonderful sights-and have nothing to regret."