My first car cost $500. It was a 1966 Ford Mustang, white with red interior. Thanks to my father, I could work on it.

That's no longer the case with automobiles. Unless you have three degrees from MIT and a trunk full of computers to plug in under the dash, it's the rare individual who can fix his own car. And that's regrettable.

After the automobile became affordable for the masses (thanks to Henry Ford), auto repair became a way for dads and sons to bond.

A father could take his son to the shade of a nearby tree and teach him how to maintain and repair his car or truck.

For most young men who lived where I did in Ashdown, Arkansas, fixing your own ride was the only way you could afford a car. Paying someone else to work on it was too expensive.

Having your dad take the time to show you how to change the oil, replace brake pads, swap out fan belts and other routine repairs was a source of pride for both dad and son. It was time together.

"If you'll just follow the instructions in the owners manual of your car, it will last a very long time," my dad told me repeatedly. "Most people do not treat their car very well. As a result, it gives them trouble. Take care of your car and it will take care of you."

He was right. He almost always was.

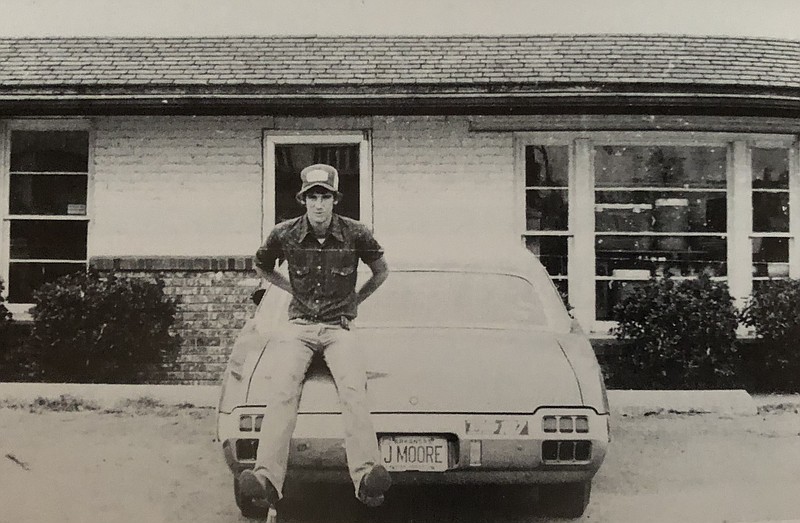

"Make sure the gap on your spark plugs is .035," dad told me, when I went from my Mustang to a 1972 Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme. "For your car to run right, you have to make sure your plugs are gapped correctly, and the timing is set right."

Again, he was correct.

I learned that an owners manual worked even better if you bought a Chilton's repair manual to go with it. There was no internet, and parts for an older car weren't available like they are today. So you had to know what part you needed, and you had to have friends at area car junk yards.

Dad and I spent many an hour scouring salvage lots for door handles, windshields, fenders, water pumps, and anything else that might need replacing on my car.

He always knew where to look and who to call.

This is how I learned the value of relationships. Today, you can order from your phone and have a part sent to you overnight. But you don't know any of the people who send you the parts.

What a disconnect. I'm not a fan of the new way of doing things.

Much like learning to be patient and wait for film you shot to arrive back in the mail so that you could see if your photos were any good, an auto parts search also required you to not be in a rush. Finding a car part you needed took time.

We often could spend an entire Saturday driving the countryside looking for a Mustang or a Cutlass that would be sitting in a field or pasture. If we saw one, we'd stop at the nearest house and inquire about purchasing a part from the car, or possibly the entire vehicle if they were willing to sell it.

It was always a bit of a scavenger hunt. A lock assembly from a passenger door might be all that was needed. But a day in the car with your dad searching, and then coming home with exactly what you'd set out to find, brought a feeling of satisfaction that I miss.

Coming home with your find was reminiscent of men of earlier eras, who would leave for a hunt and come home with enough food to feed the family for a long time. We weren't coming home with anything like that, but the feeling was similar. We'd go on a long hunt and come home with something that served us for a long time.

A repair was also rewarding. Combining maintenance with a repair was frequent.

Cars of yesteryear didn't go 5,000 or 7,500 miles between oil changes. Quaker State 10-W 30 and an oil filter were standard items, every 3,000 miles. You'd also replace all six or eight spark plugs during an oil change, and the points and condenser inside the distributor. When you were done you'd set the timing.

Checking and bleeding the brakes was done, if necessary. Rotating the tires (which was always a trick since we only had one bumper jack), and replacing the air filter were also on the list of things to do.

Maintenance like this was routine. But it also gave you a basic understanding of how an engine worked and what had to be where for things to function correctly.

Knowing how things worked came in handy one day when I was driving back home and the engine just lost power. I coasted to the shoulder and turned on my flashers. After I opened the hood, I wondered what could be wrong.

Something said, "Check the distributor." When I opened it, there it was. The negative wire to the condenser had gotten caught in the rotation of the shaft, and it sliced that tiny wire in half.

My pocket knife and some electrician's tape patched the wire. I cranked the car and was on my way.

I suspect most people today rely on a mechanic to maintain and repair their car. And that's fine. They're certified, for the most part, and know what they're doing.

But knowing how to work on your vehicle, and have your teacher be your dad, were experiences I'd not trade for anything.

Every now and then when I'm changing the oil in my truck, I think about those days. The days when the fix was in.

©2021 John Moore

(John Moore is a 1980 graduate of Ashdown High School who lived in Texarkana and worked at KTFS Radio during the 1980s. John's new book, Puns for Groan People, and his books, Write of Passage: A Southerner's View of Then and Now Vol. 1 and Vol. 2, are available on his website, TheCountryWriter.com. His weekly John G. Moore Podcast appears on Spotify and iTunes. You can email him through his website at TheCountryWriter.com.)