Supreme Court Justice Joseph P. Bradley isn't exactly a household name, but no justice has played a more high-profile role in presidential politics. After the 1876 election, newspapers labeled him "Joe Bradley, our President maker."

As the Supreme Court heard arguments Thursday on whether former president Donald Trump is immune from prosecution, the justices are under scrutiny for any role they may play in the outcome of the 2024 presidential election. But long before the court's messy involvement in this year's race or its one-vote majority that put George W. Bush in the White House in 2000, Bradley was the decider in the razor-close contest between Republican Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio and Democrat Samuel Tilden of New York. The justice became the poster boy - and, to many Democrats, the villain - on a commission created by Congress to resolve one of America's most convoluted presidential elections ever.

The outcome was still up in the air on Jan. 29, 1877, nearly 12 weeks after the election, with Tilden one short of the 185 electoral votes needed. Twenty electoral votes were still unresolved because of competing submissions from South Carolina, Louisiana and Florida - where White Democrats had attacked Black Republican voters, prompting charges of interference - and from Oregon, where one electoral vote was disputed.

Nobody knew it at the time, but the process for deciding the election would end up destroying the rights of Black people in the South. For now, the focus was on picking a president before the March 5 inauguration.

So Congress created a 15-member electoral commission, consisting of five senators, five House members and five Supreme Court justices. The members were split evenly between Republicans and Democrats, plus Justice David Davis, a political independent. But then Davis, of Illinois, resigned to accept an appointment to the U.S. Senate as a Democrat.

To replace him, the commission turned to Bradley, a moderate Republican appointed by outgoing President Ulysses S. Grant, as the least partisan of the remaining justices. The 63-year-old Bradley, a former farm boy who became a wealthy New Jersey railroad lawyer, would be the potential tiebreaker.

Bradley was a "cold man" who "convinces by the force of his argument rather than captures by the brilliancy of his rhetoric," the New York Herald wrote. "His mind is eminently judicial."

The panel began public hearings on Feb. 1 in the Supreme Court room at the Capitol. (The court didn't get its own building until 1935.) Justices on the commission didn't dress in their usual black robes and "look odd without their gowns," the New York Times observed.

Florida's four electoral votes were the first up for debate. Bradley allegedly planned to back the legitimacy of the Democratic electors, making Tilden president, a Democratic congressman from New Jersey later alleged, but changed his mind at home that night under pressure from Republican friends. Bradley denied those claims. His vote created an 8-7 majority to accept Florida's electors for Hayes.

Next up was Louisiana, and all eyes were on Bradley. "He is generally regarded as the man on who the whole thing turns," the Louisville Courier Journal wrote. The justice again led an 8-7 vote for the eight Hayes electors, augmenting Democratic doubts about his objectivity.

Sure enough, Bradley joined the 8-7 majority to award Hayes one disputed electoral vote in Oregon and seven in South Carolina, effectively electing Hayes president unless Congress rejected the results. Furious Democrats focused their anger on the head of the vile "Bradley Tribunal." Democratic newspapers sprinkled their pages with epithets about the justice: "The American Judas-Bradley." "The umpire who stole a Presidency." "Captain Kidd would have been a better man than Bradley in his place."

The New York Sun wrote that the Washington Monument should be torn down and the stones piled up again, and "at the top of all put a colossal statue of Joe Bradley, the President-maker," with "his hand stretched out toward the White House."

"Somebody tied crape to the doorknob of perjured Bradley's residence in Washington, and with it a slip on which was written, 'Justice is dead,'" the San Francisco Examiner reported.

"The abuse heaped upon me" is "almost beyond conception," Bradley wrote. His son Charles later wrote that his father was "threatened with bodily injury, aye, even to the taking of his life."

On Feb. 27, the commission sent its rulings to Congress. There was no problem in the Republican-controlled Senate, but late on March 1, House Speaker Samuel Randall (D-Pa.) banged his gavel to head off demands by some angry fellow Democrats to start a filibuster to delay the results. Rep. George Beebe (D-N.Y.) "came climbing over the tops of desks, knocking books and ink bottles on the floor, [and] shook his fist at the speaker," the Chicago Inter-Ocean wrote.

At 4.05 a.m. on March 2, senators came to the House floor for a joint session of Congress. Five minutes later, the president of the Senate announced Hayes had won the presidency, 185 electoral votes to 184. Hayes received word of his victory by telegram while on a train to Washington. The next day - a day before the official start of his presidency, which fell on a Sunday - he took his first oath of office in the Red Room in the Grant White House.

What wasn't reported was that allies of Hayes had begun secret meetings with some Southern Democrats. On April 24, President Hayes announced the withdrawal of federal troops from two Southern statehouses as part of what some historians called the Compromise of 1877. It effectively ended federal Reconstruction, which had already been weakened as Democrats took control of eight of the 11 former Confederate states.

Black citizens in the South still pressed to save their rights. Bradley would once again stand in their way. In 1883, he wrote the majority Supreme Court opinion striking down the Civil Rights Act of 1875, opening the door for Jim Crow laws and racial segregation in the South. (In 2021, Bradley's alma mater, Rutgers University, removed his name from a campus building.)

To avoid another electoral commission fiasco, Congress passed the Electoral Count Act of 1887, requiring the counting of electoral votes in a ceremony presided over by the vice president.

Bradley's influence rose again on Jan. 6, 2021, when defeated president Donald Trump demanded, without legal basis, that Vice President Mike Pence refuse to accept some states' electoral votes in the ceremony at the Capitol. In a letter to Congress, Pence promised to honor his constitutional duty, noting: "As Supreme Court Justice Joseph Bradley wrote following the contentious election of 1876, the powers of the President of the Senate are merely ministerial ... He is not invested with any authority for making any investigation outside of the Joint Meeting of the two Houses." With Trump-backing insurrectionists attacking the Capitol and shouting, "Hang Mike Pence," the vice president accepted the electoral votes that made Joe Biden president.

In a sense, Joe Bradley was once again our president maker.

- - -

Ronald G. Shafer is a former Washington political features editor at the Wall Street Journal.

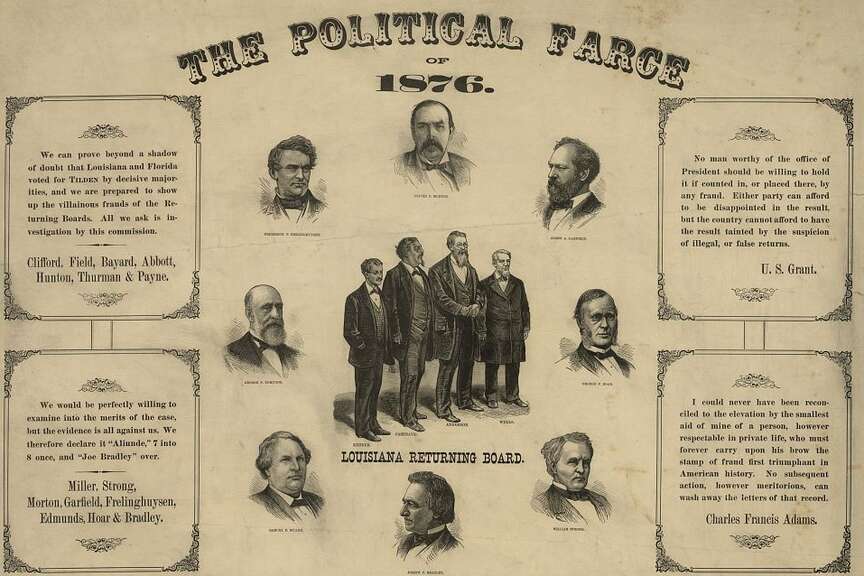

A print showing bust portraits of the eight men who helped decide the outcome of the controversial 1876 presidential election. They are, clockwise from top, Oliver P. Morton, James Garfield, George F. Hoar, William Strong, Joseph P. Bradley, Samuel F. Miller, George F. Edmunds and Frederick T. Frelinghuysen. (Library of Congress)

A print showing bust portraits of the eight men who helped decide the outcome of the controversial 1876 presidential election. They are, clockwise from top, Oliver P. Morton, James Garfield, George F. Hoar, William Strong, Joseph P. Bradley, Samuel F. Miller, George F. Edmunds and Frederick T. Frelinghuysen. (Library of Congress)