PHNOM PENH, Cambodia -- Earlier this year, the Cambodian government brought the full diplomatic weight of the state down on a seemingly slight target: a 36-year-old maid working for a middle-class family just outside Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Nuon Toeun was neither an activist nor an opposition leader. She spent her days cleaning her employer's home. She did, however, have an active social media presence on TikTok and Facebook, where she "expressed ... rage," she said, at Cambodia's elite, including its former authoritarian leader, Hun Sen, and his son, Hun Manet, the current prime minister.

The Cambodian government issued a warrant for Toeun's arrest on Jan. 18, a few weeks after she posted a video saying Hun Sen was "dancing very happily" despite the "mountain of sadness" faced by the Cambodian people: poverty, land grabs and the targeting of opposition figures. Cambodia notified Malaysian authorities of the warrant, alleging she had insulted state institutions in violation of a six-year old law that critics say has been used liberally against perceived opponents of the government.

Cambodia demanded she be returned home. But at first, it seemed as though there was little the Malaysian authorities could do. Toeun had not done anything wrong in Malaysia and had worked in the country legally for more than a decade.

It took more than six months for authorities in both countries to find a workaround. According to an internal document Malaysian immigration authorities provided to lawmakers, which was reviewed by The Washington Post, the Cambodian government in July canceled Toeun's passport and informed officials in Kuala Lumpur. Malaysia then also withdrew her work permit, making her an illegal migrant, andmonitored her on behalf of Cambodian authorities. In late September, Malaysian police arrested her at her employer's home.

Toeun was denied access to a lawyer, Malaysian lawmakers and her aunt say, and deported home two days later. She was eventually charged with incitement, the default charge used against human rights defenders, journalists and opposition figures, and has been detained without bail since then outside Phnom Penh, the capital, ahead of her trial. Relatives say she has persistent gastrointestinal issues, and has lost significant weight.

The 10 countries of Southeast Asia, which together form a union known as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), hold fast to a few principles -- noninterference in one another's internal affairs key among them. But cases such as Toeun's showcase a new kind of cooperation in the region, where governments are helping one another intimidate, arrest and extradite government critics in support of their allies' domestic agendas, according to a Post analysis of more than two dozen cases throughout the region.

In Thailand, once a safe haven for asylum seekers, Cambodian opposition leaders are routinely surveilled, jailed and deported home, where they face detention. Thai courts are also preparing to extradite a Vietnamese indigenous human rights activist who fled there to escape persecution. Malaysia, apart from Toeun's case, has deported thousands of Myanmar migrants, including defectors from the military who face certain persecution upon return.

Volker Türk, the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights, said in June that a "pattern is emerging" of transnational repression in the Southeast Asia region, "whereby human rights defenders seeking refuge in neighboring countries have been subject to rendition and refoulement or disappeared and even killed."

Seng Dyna, a spokesman for Cambodia's Ministry of Justice, said Toeun's and other cases are "currently under legal proceedings" and he could not comment specifically on them, but that the country's law "must be enforced" when there is a violation.

"The pursuit of an offender must be carried out strictly in accordance with the law, whether the offender is within Cambodia or abroad," he said. "In cases where the offender is abroad, Cambodia must seek cooperation from the relevant countries to bring the offender to justice in Cambodia."

Thailand's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Malaysian Immigration Department and spokespeople for the Malaysian government did not respond to requests for comment.

Human rights groups and lawmakers say the targeting of democratic voices has been enabled by explicit government policies, alongside deepening police and immigration cooperation throughout the region. The relatively public nature of this cooperation and the active role of state agencies is a departure from the past, when shadowy perpetrators snatched Thai opposition leaders off the streets of Cambodia and Laotian activists turned up dead in Thailand.

The targeting of democratic voices is cementing an authoritarian shift underway in much of Southeast Asia and building a state-to-state market for the exchange of dissidents and human rights defenders, lawmakers and activists say. The phenomenon has emerged over the past five years, human rights groups say, and is accelerating -- particularly in the case of Cambodian dissidents as the government in Phnom Penh, which, after crushing the opposition domestically, seeks to stamp out critical voices overseas.

Most recently, in November, Thailand deported six Cambodian activists and the 5-year-old grandson of one of them, citing immigration violations. The six, all affiliated with the now-dissolved opposition Cambodian National Rescue Party, were charged with treason upon their return to Cambodia and have been detained. The child was handed over to his grandaunt, who saidin an interviewhe neither ate nor spoke for a few days, traumatized by the separation from the grandmother who raised him.

"This is policymaking, at the highest levels," said Sunai Phasuk, the senior researcher for Thailand at Human Rights Watch, which in 2024 analyzed 25 cases of transnational repression in Thailand.

'DESPICABLE GUY'

Toeun started a new Facebook account about three years ago, after a new wave of coronavirus outbreaks forced the shutdown of Phnom Penh, and other urban areas. She was unbridled in her criticism: Hun Sen, then the prime minister, should die, she said, amid a series of expletive-laden tirades.

The tone of herposts continued in the following months and years, posted to several Facebook and TikTok accounts all under her name. In all of the videos, she faces directly to her smartphone camera, fully visible to anyone watching.

From her spartan room, she amassed a steady following among Cambodians living inside the country and migrant workers like herself.

"When people criticize the government [and] speak the truth, it arrests people, beats people and threatens people," Toeun said, using "it" to refer to Hun Sen and his family. In one of her last posts from Malaysia, she referred to Hun Sen as a "despicable guy" who has "mistreated my people so badly."

Two Malaysian lawmakers from the People's Justice Party, one of the main parties within the country's ruling coalition, pushed in November for a parliamentary inquiry on Toeun's case. Speaking before a closed-door parliamentary session, one of the lawmakers, William Leong, said he raised his concerns about the deportation process and its implications for other cases.

The Malaysian immigration authorities have also recently tried to deport a Bangladeshi opposition activist and lawyer whose passport was also canceled by his home country. Human rights lawyers argued in court that he was an asylum seeker protected by the U.N.'s refugee agency, forcing the immigration department to rescind the deportation order.

Countries in Southeast Asia, activists and lawyers say, are increasingly seeking to bypass formal extradition agreements and their protections. Malaysia, under its decades-old extradition act, can refuse an extradition if the offense is political or the person is being targeted based on their race or religion. As this transnational cooperation accelerates, those well-established laws are bypassed in favor of other -- still legal -- methods to quickly deport dissidents and activists at the request of authoritarian regional governments.

"The country of origin will say I have a right to cancel the passport; they will say [that] is a breach and I want her back," said Edmund Bon, the lawyer who acted on behalf of the Bangladeshi opposition activist.

By the time you try to appeal, Bon said, "you'll already be on the plane."

NO SAFE HAVEN

Malaysia, Cambodian opposition leaders say, is helping extend the targeting that had already become commonplace for Cambodian activists in neighboring Thailand. Cambodia held elections in July that independent observers say were neither free nor fair, citing Hun Sen's efforts to suppress the opposition through intimidation, disqualification, and arrests ahead of the vote. Hun Sen was in power since 1985 and handed the reins to his son in 2023.

The campaign sent what remained of a once well-organized and influential Cambodian opposition fleeing across the border to Thailand, some entering illegally along routes more commonly used by economic migrants.

"Thailand is our last resort ... for us, there is no choice," said Ya Kimleng, a former commune chief of her local village in Cambodia who was part of the opposition Candlelight Party. She left with her three sons after a warrant was issued for her husband's arrest. He fled to Thailand ahead of her.

The family has moved three times since arriving last year. "So we now have to live our lives in hiding," she said.

Thai authorities have helped round up prominent Cambodian activists in the country over the past year, holding them for months without bail on immigration charges. This cooperation was made public when the then-Thai prime minister Srettha Thavisin and Hun Manet met in February and promised to crack down on "interference" from Thailand-based Cambodian activists.

Ahead of that meeting, three prominent Cambodian activists were arrested and detained. In September, after Thai immigration authorities had released the three, audio leaked on Facebook and to Radio Free Asia of Hun Sen calling for one of them, opposition activist Phorn Phanna, to be returned to Cambodia "dead or alive."

"He must be brought to Cambodia. We can't let him be free. He is staging something to incite a movement," Hun Sen said, according to the leaked audio.

The audio also referred to Cambodian "forces" working with the Thai police, hinting at the presence of Cambodian agents operating in Thailand.

"If the Cambodians ask for something, it is clear the Thais will do it," said Phil Robertson, director of Bangkok-based consultancy Asia Human Rights and Labor Advocates.

INSTITUTIONAL COOPERATION

Aside from the six Cambodian activists recently deported, Thai courts are also preparing to deport an indigenous Montagnard refugee and human rights activist, Y Quynh Bdap, to Vietnam. He is a registered refugee under the UNHCR, but was arrested last June after an extradition request from Vietnam.

Indigenous Montagnards, meaning "mountain dweller," are a predominantly Christian minority who have long been persecuted by Vietnam's communist government for their role in helping American forces during the Vietnam War, their campaign for indigenous land rights and their faith. Y Quynh Bdap is a co-founder of Montagnards Stand for Justice, which the Vietnamese government has branded a terrorist organization. Human rights groups think he is at "extreme risk" of torture, enforced disappearance or other serious human rights abuses should he be deported.

Other than the courts, immigration authorities hold significant power, controlling the fates of vulnerable communities throughout the region. Since the coup in Myanmar, the ASEAN bloc has routinely condemned the ongoing violence and civil war -- a rare show of displeasure.

Yet, regional countries have not developed a cohesive or humanitarian response to the tens of thousands of Myanmar migrants who have fled, legally and illegally, to regional countries. Instead, activists, U.N. officials and human rights groups say, authorities in those countries are effectively extending the repression meted out by Myanmar, which has arbitrarily canceled passports belonging to politically active people in the diaspora or made them much harder to renew in recent months, especially in their embassies in Thailand and Singapore.

Rather than pushing back, these countries have either abided by the passport cancellations or deported refugees, asylum seekers and others with expired work permits, sending them back to situations where they face detention, extortion or forced conscription.

"The junta is getting countries to aid and abet in its repression, [and] the region in particular needs to step up," said Thomas Andrews, the U.N. special rapporteur for Myanmar.

In recent months, Thailand began an immigration crackdown against Myanmar migrants who had either overstayed their visas or entered illegally, detaining 200,000 workers -- a new high for Thai authorities, according to workers rights activists there. Many of them had fled recently either because of violence or to escape the draft, as the junta seeks to replenish its ranks after losses to rebel groups.

More than 1,000 deportees from Thailand have been forcibly recruited into the Myanmar military upon their return since July this year, said Ko Thar Kyaw, an activist focused on migrant workers living along the Thai-Myanmar border.Some were younger than 15.

"It is like our Myanmar people are orphans, he said. "We're bullied in so many ways."

------

Vicheika Kann in Phnom Penh contributed to this article.

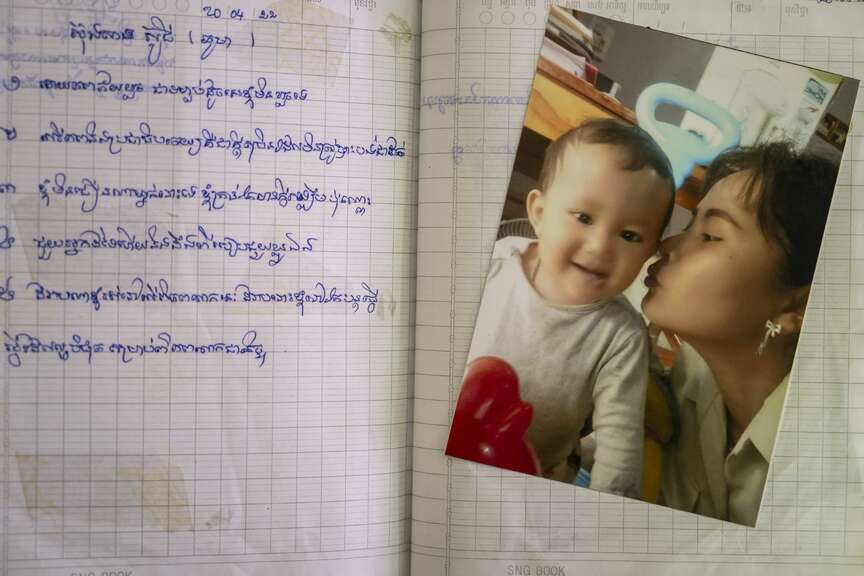

A photograph and note in a scrapbook of Lanh Thavry, 36, seen April 30 in Bangkok. She was deported from Thailand to Cambodia in 2021 and jailed. Thavry returned to Thailand after her release, but is fearful of leaving her home after recent arrests of other Cambodian activists in Bangkok. (Sirachai Arunrugstichai for The Washington Post)

A photograph and note in a scrapbook of Lanh Thavry, 36, seen April 30 in Bangkok. She was deported from Thailand to Cambodia in 2021 and jailed. Thavry returned to Thailand after her release, but is fearful of leaving her home after recent arrests of other Cambodian activists in Bangkok. (Sirachai Arunrugstichai for The Washington Post)