OUAGADOUGOU, Burkina Faso - The young West African students touched down in what was then the Soviet Union knowing only a handful of Russian words and little about their new home.

Decades later, those former students - many of whom became doctors, engineers and businesspeople in West Africa - are key influencers for Russia as it vies with the West for sway in this turbulent part of Africa. In interviews in Burkina Faso, which has become a focus of Russian outreach, the former students said they are fostering economic, educational and diplomatic ties as they help their country move away from generations of working with the West and toward partnership with Russia.

"We studied there and know the potential," said Christian Ouédraogo, who arrived in the Soviet Union in the late 1980s and now leads a Russian-Burkinabe business club. "We want to play our part - to sit down at the negotiating table and accompany authorities so that this partnership is win-win and enables real growth for our nations."

The Biden administration has been frustrated as junta officials in Burkina Faso and its neighbors have embraced warm relations with Russian President Vladimir Putin. Interviews with the former students in Burkina Faso underscored the breadth of ties with Russia, which extend beyond the security cooperation that is often the focus of Western officials.

Ouédraogo was part of a delegation that met with Burkina Faso's President Ibrahim Traoré at a Russia-Africa summit in Russia. He also launched an economics club focused on cooperation between the two countries and assisted in organizing a trip to Moscow for dozens of Burkinabe businesspeople. Other former students have helped establish clubs dedicated to Russian language and culture.

"We know Russia well - the language and the mentality," Daouda Diané, who studied hydrologic engineering in Russia and now leads a club of former students. So we are well placed to explain to many Burkinabes who are not familiar with it. We are the bridge."

RUSSIAN SOFT POWER

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union had far less than the West to offer in development aid. So one of the main ways the Soviets gained influence was through grants for students, said Ulf Laessing, the Mali-based head of the Sahel Program at the Konrad Adenauer Foundation.

From the 1960s through the 1990s, thousands of students from Burkina Faso (which was known as Upper Volta until 1984) studied in the Soviet Union and later Russia before returning home.

Across West Africa, including in Mali, former students have acted as "mediators" between Russia and their nations, Laessing said. And with Russia's military capabilities dealt a blow by the toppling of Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad, Laessing added, its soft power efforts, including ramping back up scholarships and language programs, could become even more important to Putin as he pursues global influence.

But there has been a massive knowledge gap to overcome, the former students said. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the number of foreign students studying in Russia dwindled, and Russia closed its embassy in Burkina Faso, largely turning inward.

Tatiana Gontran, a Russian woman who married a Burkinabe man in 1995 and then joined him in Burkina Faso, said that for years after she arrived, there was next to no awareness of Russia. Once, she said with a laugh, she told a Burkinabe man she was from Russia, and he asked her where in the United States that was.

Today, she is helping run La Maison Russe, or "the Russian House," which gives free language lessons to Burkinabe students applying for scholarships in Russia.

Clarisse Poda, who studied medicine in the Soviet Union and is now a gynecologist in Burkina Faso, said she and other students who studied in Russia faced stigma on returning home, sometimes, for instance, being scoffed at by doctors who had studied in France or elsewhere in the West.

"Russia has always been relegated to a second position," Poda said in a recent interview. "But it is now that the paradigm is changing ... there is a real opening."

CHANGING TIMES

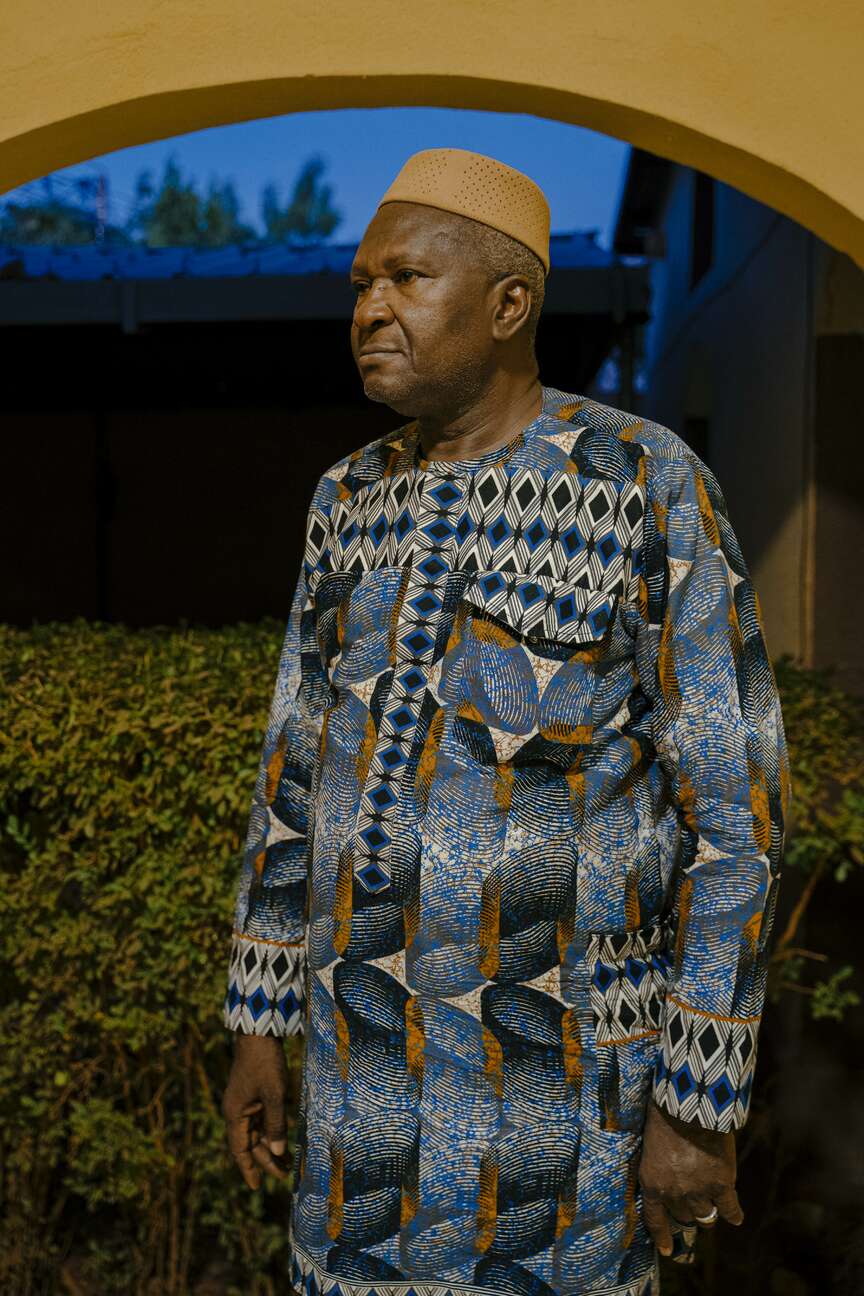

On a recent day in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso's capital, businessman Boureima Sangaré was sitting at his desk, taking a call in rapid-fire Russian about sesame that he was helping Burkinabe farmers export to Russia. On his desk was a bottle of organic Russian fertilizer that he hoped farmers would soon use.

Sangaré studied in Russia for nine years starting in 1974. He said that he faced far less racism there than in France, Burkina Faso's former colonial ruler, and that he thought Russians, unlike the French, were able to see Burkinabes as equal partners. In 2023, he led a delegation of Burkinabe businessmen at a Moscow economic fair, which he said marked the beginning of what they hope will be flourishing business ties.

"It has changed a lot and it has changed fast," Sangaré said of the connection between the two countries. He credited Burkina Faso's president, who has been a staunch proponent of working with Russia.

Today, Russian flags fly at traffic circles in Burkina Faso's capital and graffiti depicting Putin is commonplace. Inside a small, tree-shaded building on a recent day, a group of young Burkinabes sounded out words in Russian as they followed along during an online lesson. All were hoping to apply for scholarships in Russia, and some already had.

In the class was Nikiema Moise, who said he loves Russia so much that his friends call him "Putin." He said he hopes to go to Russia to study math.

"Russia is giving opportunities. It is the only country I know that is doing so," he said.

Evgeniya Tikhonova, the head of the Russia House, compared the organization to China's Confucius Institute, saying the idea was to spread language and culture.

Tikhonova, who said the center is privately run, said classes like this one are intended to remake the "deep connections with Africa" that had been fostered under the Soviet Union.

"It is high time to rebuild it again," she said. "To show that Russians are not aggressors but here to help and be hospitable."