True Love

by Sarah Gerard; Harper (224 pages, $25.99)

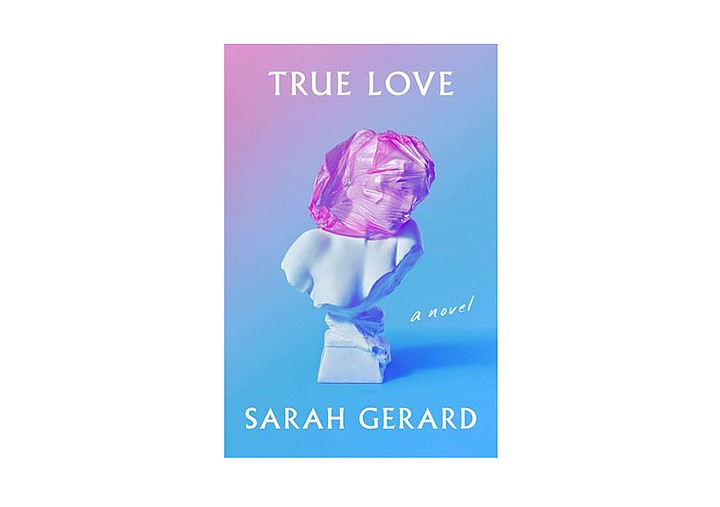

Don't let its pastel pink-and-blue cover fool you. Sarah Gerard's new novel, "True Love," is about as far from a standard rom-com as a book can get. It's acerbically funny and sharply observant, but this tale of romance among millennials is more bleak than bubbly.

This is Gerard's second novel, after "Binary Star" (2015). Her critically acclaimed 2017 essay collection, Sunshine State, combined reported essays and memoir for a keen and disquieting portrait of Florida.

The first part of "True Love" is set in St. Petersburg, to which its narrator, Nina, has returned after dropping out of college in New York City and spending eight weeks in rehab for a laundry list of addictions and self-harming behaviors.

Various stints in therapy and rehab have made her skillful at analyzing her own and other people's emotions and taught her a vocabulary for cracking wise about it: "At the moment, Jared is mansplaining polyamory, and I am performing compassion through active listening."

But her skills don't yet extend to changing some of the toxic stuff in her life. She can't quite extricate herself from her relationship with her mother, who vacillates between chilling rejection of her daughter and smarmy attempts to reconcile. "Those who know her," Nina tells us, "know that beneath her anger is tenderness, and beneath her tenderness is fury."

After Nina's parents' acrimonious divorce, her mother "has since moved to a nudist colony in Kissimmee to live with her polycule." (If you haven't had polyamory mansplained to you, that's a connected network of nonmonogamous relationships.)

Nina's sex life may be even more complicated than her mother's. In St. Petersburg, she's in a long-term relationship with the emotionally distant Seth, although she's a lower priority for him than his artwork. He's more poseur than artist, though - as one of Nina's friends says of his exhibition, "Did Seth really think someone would want to buy a kid's homework he found in the garbage?" - and he's more mooch than either.

Despite her near-obsession with Seth, Nina is constantly pursuing sex with other men. On the novel's first page, as she's talking with a friend on the phone, she's sexting intimate photos of herself to Brian, the editor of an alt-weekly she writes for, with whom she's having an affair that she's hiding from Seth. Like all of the book's sex scenes, this one is explicit but emotionally cool, as if Nina is more observer than participant.

And like much of her sex life, it's conducted with the aid of technology. Texts, social media, emails, voicemails, videos - for Nina and her friends and lovers, they're means of communication that can also be traps. At one point, Nina learns that a former lover has circulated a revenge-porn video of her. When she asks a friend what website it's on, the friend replies, "It doesn't matter. The internet is forever." (If, like me, you are a reader of a certain age, you might find yourself grateful that our wild days happened before devices ate everyone's privacy.)

When Nina moves back to New York aiming to restart her writing career, Seth tags along, and Gerard gives readers an unflinching look at the grim economics of being a struggling artist of any kind. Among other, more transient jobs, Nina works as a personal assistant to a bestselling writer, then as a bookstore manager, eventually going back to school to earn her MFA. All the while she's supporting Seth and living with him in a claustrophobic apartment where the only way Nina can find privacy to write is by locking herself in the bathroom.

Nina and Seth break up after she starts another relationship with Aaron, an old college friend and an aspiring screenwriter. Nina and Aaron move into an even tinier apartment and an even more dependent relationship. Then, in a bout of optimism, they elope: "We take our place in the Marriages/Deaths line at the Brooklyn courthouse. I wear a cream cotton dress I'd had since high school, when I stole it from the Charlotte Russe in Tyrone Mall."

In rom-coms, the wedding is usually the happy ending. In "True Love," not so much.